Beverley Boy: Soldier 452

- JillAnsell

- May 17, 2017

- 3 min read

This belated post is the final version of a work I started last year while on a residency in Beverley and then sold at the Skin Deep Exhibition early this year. I was happy with the work and wanted to share the back story.

Beverley Boy: Soldier 452

Soldier 452 is my Grandfather, Fred Hobbs. Like so many of the stories of soldiers that went to the Great War, his story is simultaneously unremarkable and remarkable. Unremarkable in that horrors he went through were shared by so many; and remarkable because he survived.

He was born in Devon in 1894, and with his brother Dick travelled to Western Australia. They joined their older brothers, Bill and Jack, who had found work and opportunity here. When WW1 broke out Fred and Jack signed up early in 1915 in the second of the West Australian Battalions, the 28th. They arrived at Gallipoli in September 1915. Here Fred contracted Enteric Fever (Typhus) and was sent back to Australia.

Back in Australia Fred convalesced in Beverley staying with his brother Bill (who had been ‘manpowered’ as a farmer at the start of the war). An unknown person sent Fred a white feather. Offended, he responded by donning his uniform on a Saturday morning and marching up and down the main street of Beverley to prove he was a soldier on sick leave and not a coward. Soon after he had recovered enough to be sent back to join his brothers on the Western Front.

With the benefits of hindsight, being out of the front line in 1916 was no bad thing for Fred. The 28th Battalion was slaughtered at Pozieres. When Fred got back to the Battalion at the start of 1917 it was in time for another famous defeat at Bullecourt. Both Fred and Jack got a ‘Blighty’ (an injury that was bad enough for them to be sent back to England to recover). Fred was shot in the knee whilst Jack was caught by shrapnel in the thigh. Their other brother Dick was uninjured.

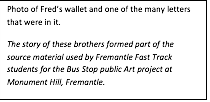

Patched up again and sent back to the front, Fred’s war ended outside a small village called Framerville. He was digging in on the evening of the 10th of August when he got hit by a bullet on its way towards his heart. As luck would have it, he had a large wallet chock full of letters and photos in his front breast pocket. This took the direct hit and sprayed the bullet across his chest, whilst another bullet went through his knee.

Badly wounded, he couldn’t walk. But he could see; and another man who had been blinded could walk. Together they got back to the advanced dressing station. Fred was left outside for the night after being assessed as having little chance of surviving. When he was still alive in the morning they packed him off to England – and out of the war. He survived, as did his brother Dick. Jack and their cousin Billy were not so fortunate.

Other than the wallet that saved his life, Fred had another souvenir – a battered tobacco tin that took a hit in the back pocket for him at Bullecourt. This portrait of Fred as a young soldier is in a tobacco tin and includes other fragments to signify objects that saved his life.

Notes abridged from an article by David Ansell and information from Dorothy Ansell (Hobbs)

Comments